The passing of Dave “Devilfish” Ulliott earlier this week brought to mind his significant role on the first series of

Late Night Poker. That in turn reminded me of a lengthy interview I was able to do a while back with Jesse May, another person who was there at the start of the groundbreaking poker TV show in the late 1990s.

This was another of those Betfair Poker interviews that are no longer available online, and I realized now might be as good a time as any for me to repost the interview over here. Took me a while to find the sucker, actually, but thankfully I did.

I’ll repost it here in two parts, just as it originally appeared on Betfair Poker in early April 2011 -- right before Black Friday, actually, which is kind of interesting to consider when reading some of the discussion of the state of poker at that time. The first part primarily focuses on May’s 1998 novel, Shut Up and Deal, while the second (which I’ll post tomorrow) delves into the Late Night Poker story.

Thanks again, Jesse, for the interview!

* * * * *

“The Betfair Poker Interview: Jesse May, Part 1”

[Originally published at Betfair Poker, 1 April 2011]

When it comes to poker-themed novels, Jesse May’s

Shut Up and Deal (1998) stands out as an especially accomplished entry, a book that brings alive the unique and fascinating world of the cash-game grinder of the mid-1990s.

May’s narrator, a young poker pro named Mickey, relates in episodic fashion the story of his ongoing struggles both at the tables and elsewhere, exploring in detail the many challenges faced by himself and others as they all separately strive to “stay in action.” Full of memorable characters and set pieces, I highly recommend May’s novel as both an entertaining read and an insightful exploration of poker’s many highs and lows.

In addition to his poker writing, May is well known for his contributions as a commentator on numerous poker shows, a role that has earned him the nickname “the Voice of Poker.” For May that career began shortly after the publication of his novel with the first season of Late Night Poker (in 1999), a show that would come to have great influence on televised poker a few years later with the launching of the World Poker Tour and expansion of coverage of the World Series of Poker on ESPN.

I recently had the opportunity to talk with May about both Shut Up and Deal and the early years of Late Night Poker. This week I’ll share the first part of our conversation in which we focused on May’s novel, and next week will present the story of May’s involvement with Late Night Poker.

Short-Stacked Shamus: I know Shut Up and Deal is based somewhat on your own experiences playing poker in the late ’80s-early ’90s. To what extent is Mickey’s story comparable to your own?

Jesse May: First of all, the story is true in the sense that I think truth is stranger than fiction. When I was writing it, I wasn’t worried about it being true, but I think that when it comes to a lot of gambling stories, you find that you could never make this stuff up. That’s been the case, I think, for every moment I’ve been in the gambling world.

Like Mickey, I did start playing when I was in high school. With a couple of other guys we all got obsessed with poker at the same time, then went out to Las Vegas -- four of us, all underage, like 17 or 18 -- and there discovered Texas hold’em (limit). Soon after that it became kind of a more serious thing for me. I used to go to Las Vegas quite a bit back before I turned 21, spending summers there trying to play poker. I dropped out of college twice, and after I turned 21 I ended up in Vegas and really tried to make a go of it.

Obviously it was during that poker explosion, and so as far as the places in the book go, they did kind of coincide with where I was. I spent a lot of time in Las Vegas. I was in Foxwoods within a month after they opened up [in 1992] and stayed there the better part of a year. I was in Atlantic City the very day they opened poker [in 1993], and stayed there about a year-and-a-half. Those were really interesting times as far as poker goes, because it was so new. There was no internet, obviously, back then, and all the action was there. I think the world had never seen anything like those two major openings -- Atlantic City and Foxwoods.

SSS: In a way the novel kind of chronicles this interesting and important moment for poker. For a lot of people who only came into poker post-Moneymaker, they might not realize how significant that earlier “explosion” really was for poker.

JM: That’s true. Also, it was interesting... at the time there were some poker texts, but most people really didn’t have access to them. So it was a combination of there being so few people who played poker -- not even well but just marginally -- and there being so much money around.

It was incredible, because it required such a different skill set to become a poker player then -- a professional -- than it does today. The skill sets then were really about money management and surviving in that hustling type of world rather than sitting around talking about hands. People didn’t sit around and talk strategy then. You talked about who was cheating and who owed you money and that kind of stuff (laughs). And I loved that world, and so for me it was a great time.

SSS: It’s funny, the world your describing was really much more similar to what came before -- even stretching back to the 19th century -- than what the poker world has become over the decade.

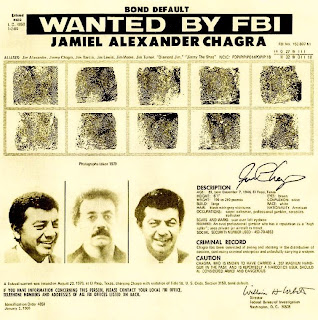

JM: It’s true. I look at a guy like Amarillo Slim [Preston]. You know -- throw out all the personal controversies that he’s had -- people have been very critical of his game, saying that he’s essentially not a poker player. And to some extent that’s true, but the fact is that in his time, and even when I would play with him a little bit back in Foxwoods, he was representative of a guy who was a great professional as far as poker went. Because he knew everything else. He knew how to get a game together, how to get an edge... he knew all that stuff. And I always had a lot of respect for him.

It was people like that -- like the Bart Stone character [in Shut Up and Deal] -- who really were able to thrive back then, and who wouldn’t be thriving now. And it really was, as you’re saying, the tail end of that era where that sort of “road gambler” was able to succeed.

SSS: So what led to your decision to write the novel?

JM: The book itself was written as a catharsis, really. Back when I was playing, you got such a strong response from people when they found out you were playing poker. You kind of continually felt yourself defending your lifestyle to others and to yourself and trying to make order of it.

I used to take a lot of breaks when I played poker, and this particular time when I had the first crack at writing the novel, I had been playing in Atlantic City and took off nine months to travel in Asia. It was during that period I wrote the bones of the novel, writing every day.

SSS: So the places and chronology of the novel roughly correspond to your own experiences. The characters -- Bart Stone, John Smiley, Uptown Raoul -- I assume they, too, are somewhat based on people you knew and with whom you played?

JM: Yes. Actually there were some liability issues with the publisher that made it very important for me to go through and change certain things -- ethnicities, physical qualities, names, things like that. But a lot of times [with a given character] there was some person I had in mind, and sometimes characters were compilations of different people.

The Bart Stone character, for example, was probably as close to real as you could get [i.e., the person on whom he was based]. He was such a strong personality, you couldn’t exaggerate him. His life was so amazing... he really was one of the true road gamblers. He was a guy who had a church-going wife and completely lived this sort of “picket fence” existence for three weeks out of every month, then for one week he’d get into his car to some town -- just start driving -- and find a town, find a game, and find a way to get the money.

He had this saying. He said he’d go into a town and first he’d try and beat people on the square. If that didn’t work, he’d try and cheat them. And if that didn’t work, he’d just pull out a gun and rob the motherf*ckers. That was his philosophy of life!

SSS: You actually start the novel with Bart Stone -- with a sketch of his character and telling the story of him cheating others. It’s interesting, because I think by starting the book that way you kind of indirectly introduce Mickey as a contrasting figure -- a “good” guy, that is, who looks at Bart and expresses a kind of awe because he could never live that way. But then he weirdly admires Bart, too. And Mickey, as we come to find out, isn’t without flaws himself.

JM: I guess it’s kind of flattering to hear you say that. You know, I recently just read Vicky Coren’s book. I don’t know if you’ve read that.

SSS: Oh, yes -- For Richer, For Poorer. It’s terrific.

JM: Yes, I quite like it, too. And I think the reason I like it so much is that unlike a lot of these “tell-all” poker books or whatever they are, Vicky never tries to make herself into sort of an elite. She throws herself in with the poker players -- they are her peers, and she’s not trying to pretend that she’s not as bad or as good or as sick or as addicted or anything as any of them. And I always thought that was kind of important in the poker world as far as keeping your own order together was concerned -- that if you do think you’re different or better than everyone else, at least recognize that you’re a hypocrite (laughs)!

One of the things about poker, especially back then, is that you are faced with so many moral choices. I think that’s what excited me about the story more than anything else. Just because of poker’s nature, the decisions that you have to make every day... you are constantly testing out your own morality. And other people’s, too. You find out a lot about what lengths they’ll go to, what depths they’ll sink to, really who they are as a person. Poker reveals so much about people’s personalities because the ethical dilemmas -- the gray areas -- they come so fast and furious.

SSS: There are several themes present in the novel. One seems to be the way people tend to view poker either realistically or they romanticize it -- that there’s a “reality” of poker that some get, and there’s a “romance” about the game that others prefer to see.

JM: I’ll buy that.

SSS: A related theme in the book -- and this is interesting because you’ve already used this phrase a couple of times with regard to the writing of the novel -- is this idea of “making order” of your life. Mickey is constantly trying to do that himself in the book, and struggling, at times, between being “realistic” and being “romantic” about his life as a full-time poker player.

JM: I think that for people who play poker professionally today, that “order” is so much more readily available. And it’s an order that is very similar for all of them. They’ve identified profitable ways to play, mistakes their opponents make, and all of the numbers involved that they can see with the tracking software and things like that -- the order is there. I think it was much harder before, but believe me, they still have a lot of chaos in their lives, because the nature of poker and gambling is obviously based on the streaks of winning and losing. That stuff throws off your sense of balance.

Then there’s the “moral” order of setting up rules for yourself, which obviously is a whole other thing. The order of believing that what you’re doing is the right thing to be doing. To me that’s always been the major theme of gambling -- not just poker -- that you’re always making up new rules for yourself. Maybe it’s like that in life, too, you know, something works for a while and then something throws it off and you have to go back to the drawing board. But it’s very important for people to have a sense of order, and I agree that’s something that Mickey struggles with in the book. As everybody in the poker world does.

I think everyone takes this little, sort of vicarious pleasure in seeing someone who’s completely on top of the poker world run bad. You know, when somebody like Brian Townsend is writing that he’s questioning everything and going back to the drawing board. You recognize that the poker world can be as chaotic for them as it is for the rest of us.

SSS: I think you’re right about it being a different situation today than for players in the ’90s, not just in terms of being able to track results and see “order” that way, but when it comes to the moral questions, too. Poker still isn’t completely accepted today, but -- to go back to what you were saying earlier -- poker pros aren’t necessarily having to defend what they do as much today as before.

Okay, one last question about the novel. What writers -- poker and otherwise -- would you list as ones you admire and might consider as having influenced you when writing Shut Up and Deal?

JM: As far as poker writers are concerned, I love Al Alvarez (The Biggest Game in Town), of course. And Jon Bradshaw, I love the way he profiles people in Fast Company. Also, Damon Runyon, to me, is one of the great writers of all time when it comes to creating the characters of gambling. I feel like he is so underappreciated, although now that I think about it I probably never read any Runyon before I wrote the book. And Mario Puzo’s Fools Die...

SSS: You allude to that one in Shut Up and Deal.

JM: Oh, that’s right. You know Puzo was a big gambler. To me, Fools Die was the greatest book on Vegas that had ever been written. There are a couple of scenes in there in which he describes Vegas that I think heavily influenced me.

For other [non-gambling] stories, I used to read Somerset Maugham quite a bit. I love storytellers who are happy to tell the details they want to tell, you know? Writers like Hemingway or Djuna Barnes... who show that it doesn’t have to be a [linear] sort of narrative where you say “he said” and then “she said” but that you can just relate what strikes you about people. I always felt like that at the poker table, but essentially there you are just watching people, which I love to do.

Come back tomorrow for Part 2, covering the early years of Late Night Poker.

Labels: *by the book, Al Alvarez, Amarillo Slim Preston, Dave Ulliott, Fast Company, Jesse May, Jon Bradshaw, Late Night Poker, Mario Puzo, Shut Up and Deal, The Biggest Game in Town, Victoria Coren