Forcing One's Hand: Dostoevsky's Crime and Punishment

Excellent summary of the craziness at Bodog (or “New Bodog”) over at Kick Ass Poker. Sounds a lot like Bodog’s primary crime was simple negligence, with perhaps an added dash of arrogance (Ayre-o-gance?). Thus does the punishment -- that 12-hour interruption of service that occurred a couple of days ago, the permanent loss of their domain, the headache of getting everyone pointing to them to update links, etc. -- appear harsh, though some might believe not entirely undeserved.

Excellent summary of the craziness at Bodog (or “New Bodog”) over at Kick Ass Poker. Sounds a lot like Bodog’s primary crime was simple negligence, with perhaps an added dash of arrogance (Ayre-o-gance?). Thus does the punishment -- that 12-hour interruption of service that occurred a couple of days ago, the permanent loss of their domain, the headache of getting everyone pointing to them to update links, etc. -- appear harsh, though some might believe not entirely undeserved.Speaking of crime and punishment . . . .

Last summer I wrote a few posts discussing Fyodor Dostoevsky’s The Gambler (1867). That novel comes up frequently in poker narratives -- Alvarez, Spanier, Holden, McManus all refer to it -- and in those posts I considered a few reasons why I thought it of particular interest to poker players. (If you’re interested, those posts begin here.)

Dostoevsky is also an author of relevance to anyone interested in existentialism, as his novels provide ideas and arguments picked up and elaborated upon by later writers (both philosophical and literary) who operate within that tradition. Of course, it would be anachronistic -- and inaccurate, really -- to refer to Dostoevsky as an “existentialist.” Nevertheless, many of his characters express what can be called existentialist views, and he is often regarded as a kind of precursor to the movement. (E.g., Walter Kaufmann calls Dostoevsky’s Notes from the Underground “the best overture for existentialism ever written.”)

And, of course, when it comes to Dostoevsky’s Crime and Punishment (1866) -- a dark, violent, gripping murder mystery with alarming plot twists over which hangs a haunting, fatalistic ethos -- we’re also edging over into “hard-boiled” territory as well.

Makes sense, then, that I’d be getting around to posting something about this novel here sooner or later.

I really just wanted to share one, brief passage with you that illustrates a state of mind I myself have experienced while playing poker -- one that I think is not uncommon at all. It happens relatively early in the novel, just as the main character, Rodion Romanovitch Raskolnikov, has begun to formulate his plan to kill and rob a local pawnbroker named Alyona Ivanovna.

The notion to commit such a ghastly crime had only just occurred to Raskolnikov after meeting the pawnbroker to negotiate the sale of a few items. As Dostoevsky tells it, “A strange idea was pecking at his brain like the chicken in the egg, and very, very much absorbed him.” In this distracted state, Raskolnikov finds himself within earshot of a pair of students playing a game of billiards. Gradually he realizes the young men are discussing Alyona Ivanovna, the very woman over whom Raskolnikov had been brooding.

Suddenly one of them claims he “could kill that damned old woman and make off with her money . . . without the faintest conscience-prick.”

Raskolnikov shudders at the uncanny coincidence of hearing these men discuss so casually what he himself was considering. The braggart goes on to say how he believes killing the pawnbroker would be justified. “Besides,” he says, “what value has the life of that sickly, stupid, ill-natured old woman in the balance of existence?”

Here’s how Dostoevsky describes his protagonist’s state of mind after having overheard such a proclamation: “Raskolnikov was violently agitated. Of course, it was all ordinary youthful talk and thought, such as he had often heard before in different forms and on different themes. But why had he happened to hear such a discussion and such ideas at the very moment when his own brain was just conceiving . . . the very same idea? And why, just at the moment when he had brought away the embryo of his idea from the old woman, had he dropped at once upon a conversation about her?”

Obviously killing the pawnbroker is a bad idea. And it hardly resembles, say, decisions one makes during a hand of Hold ’em. There is a connection, however, I’d like to draw . . . an application of sorts of a principle found here to what can happen at the poker table.

I am referring to this notion of developing a theory independently -- something yet to be tested adequately by experiment -- and then just as one is about to try it out, hearing someone else endorse the very same idea. Such a theory (however valid) swiftly becomes almost irresistible.

Ever go through that in yr development as a poker player? Say you’ve just started playing limit Hold ’em and have developed certain notions regarding middle pairs like 77, 88, and 99. You’re losing with those hands, but starting to think maybe you should begin raising preflop every time to weed out the field, then pushing with them as though you held AA and see what happens.

Then you find yourself in a bookstore with a copy of a certain well-known, successful poker pro’s book in your hands. You happen upon his suggestion to beginners always to raise with 77 regardless of position and “no matter what it costs you to get involved.”

You’re done for. Your will is no longer entirely your own. As Dostoevsky says a bit earlier of Raskolnikov, “he felt suddenly in his whole being that he had no more freedom of thought, no will, and that everything was suddenly and irrevocably decided.” That strange idea pecking in yr egghead has broken through. You’re gonna try it out . . . and it might work for you. Regardless of what happens, that affirmation-before-the-fact has filled you with a false confidence, or at least a sense that your subsequent actions are somehow justified.

Probably a better way to describe the phenomenon would be simply to refer to those moments when you tell yourself “I have to [fill in the blank]” at the poker table. We’ve all been there. “I was getting 5-to-1, so I had to call.” We forget -- a lot -- that we never have to do anything in a given hand.

But often we tell ourselves otherwise. Theory overwhelms practice. Again and again.

So if you haven’t read it, go check out Crime and Punishment -- especially if you have an interest in existentialism and/or “hard-boiled” plots and characters. Or even if yr just looking for a compelling murder mystery that forces you to think about the many factors -- most out of our control -- that tend to motivate us poor, flawed humans to action.

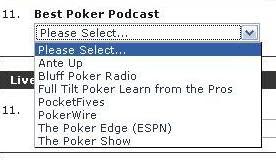

Meanwhile, I’ll be following tonight’s final table of the WPT Legends of Poker Main Event at the Bike, where two of my favorite poker authors, Tom Schneider and Dan Harrington, have most of the chips heading into play. CardPlayer has bought exclusive rights to reporting WPT events, so we gotta head over there to follow along.

Dunno about you, but I’m hoping Tom schneiders them.

Labels: *by the book, Crime and Punishment, Fyodor Dostoevsky

. Both the short stacks fold, and Moosehead completes from the SB, I raise it up to 300, and Moosehead calls. Flop is

. Both the short stacks fold, and Moosehead completes from the SB, I raise it up to 300, and Moosehead calls. Flop is

and Moosehead instantly bets pot -- 600 chips. He’s got 4,730 behind, and I’m sitting there with 3,180.

and Moosehead instantly bets pot -- 600 chips. He’s got 4,730 behind, and I’m sitting there with 3,180.

. I’m still about 42%, though. But the river is the

. I’m still about 42%, though. But the river is the  , and I’m out in 4th.

, and I’m out in 4th.

. My initial flicker of interest was quickly extinguished when the UTG player bet pot (360) and UTG+1 quickly raised pot (1,440 more). Seemed possible I’d be drawing nearly dead here with my middle set, so I let it go. Those two got it all in, and it turned out neither had the set of eights -- UTG had

. My initial flicker of interest was quickly extinguished when the UTG player bet pot (360) and UTG+1 quickly raised pot (1,440 more). Seemed possible I’d be drawing nearly dead here with my middle set, so I let it go. Those two got it all in, and it turned out neither had the set of eights -- UTG had

(an overpair and a jack-high flush draw), while UTG+1 had

(an overpair and a jack-high flush draw), while UTG+1 had  (a worse flush draw and a backdoor dream or two). Would’ve been ahead (but vulnerable), had I stayed in. The bigger stack ended up taking the pot -- and a sizable chip advantage over the table -- and we were down to four.

(a worse flush draw and a backdoor dream or two). Would’ve been ahead (but vulnerable), had I stayed in. The bigger stack ended up taking the pot -- and a sizable chip advantage over the table -- and we were down to four.