Poker players are familiar with how the game often fools us with regard to our own abilities. The game’s not insignificant chance element can confuse even the most level-headed when it comes to understanding what we’ve accomplished (or failed to accomplish) when we play. Indeed, a big part of poker is the way it forces us to think about how we measure ourselves -- both what we’re capable of, and what we’ve ultimately done.

Yesterday I ended up spending some time thinking along these lines -- i.e., with regard to human psychology and ideas about what humans are capable of doing -- though the cause and context of these musings weren’t poker-related, but rather brought on by something else.

I ran across a reference to the fact that the 45th anniversary of Tommie Smith and John Carlos’s “black power salute” on the podium at the 1968 Summer Olympics in Mexico City had come on Wednesday.

That got me reading around about the event and before long I was reading about a 2008 documentary titled Salute. The film tells the story of the event while also bringing to the foreground the role played by the other person standing on the podium, the Australian sprinter Peter Norman, who took silver while Smith won gold and Carlos bronze. Discovering the film streaming on Netflix, I took a look.

Having followed the battle over racial equality in the U.S. while also witnessing similar strife in his own country, Norman supported the American sprinters’ protest. Like Smith and Carlos, Norman wore an Olympic Project for Human Rights button on the dais. The OPHR was an organization founded by the sociologist Harry Edwards in order to protest racial segregation in the U.S., and had even proposed and backed an ultimately unrealized plan for black athletes to boycott the ’68 games.

Norman’s wearing of the button was an unambiguous indication of his support for what many regarded as an outrageously defiant act made by the men standing behind him during the playing of the American national anthem. As the film shows, Norman’s support wasn’t idly given, but the product of his own well-nurtured beliefs in human rights and equality. Salute also explains how like Smith and Carlos, Norman suffered repercussions for action that day and for his statements afterwards in support of the Americans’ protest.

The film is fairly riveting, including lots of primary footage as well as lengthy contributions from all three runners. It was made by Norman’s nephew, and there might be a moment or two where that fact might enter into one’s thinking during the uninterrupted championing of the Australian runner.

But Peter Norman is so unassuming and modest in the film -- and especially persuasive when even-handedly explaining his unwavering humanitarian beliefs -- it’s hard not to come away liking him a lot, and perhaps even being inspired, too. (Norman died in 2006.)

After the film was over, I found myself going back to a favorite sports moment of mine, Bob Beamon’s electrifying world-record long jump at Mexico City that happened two days after the protest -- i.e., 45 years ago today. The protest during the 200-meter medals ceremony was shocking to many, for a variety of reasons. But Beamon leaping 29 feet, 2½ inches was just plain staggering.

I remember as a kid being fascinated with the picture of Beamon hanging in the air in

The Guinness Book of World Records, knees up around his chest, arms extended like wings. I love watching

YouTube clips of the jump, and don’t think I’ll ever tire of doing so. He bounds through space, lands and immediately springs back up out of the dirt and jumps again. And again. Then jogs around in a way that almost looks like he’s dancing a little.

He has no clue what he’s done.

Afterward Beamon explained “it felt like a regular jump,” although he knew it was good and perhaps even a record-breaker. But it was hardly a regular jump.

When Ralph Boston had broken the 25-year-old record in 1960, his 26’11” jump set a new standard by a couple of inches. The record had then literally inched upward over the next several years, with Boston and Igor Ter-Ovanesyan having each made it to 27’4½” by 1967.

Now Beamon had shattered the record... by nearly two feet!

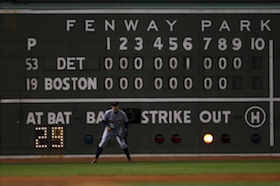

It took several minutes to measure the jump, as Beamon had gone farther than the optical measuring equipment was set up to record. Then when a figure of “8.90” was finally posted on the scoreboard (representing meters), Beamon still didn’t know immediately what that meant as far as feet and inches went.

Boston -- the former record holder, 1960 long jump gold medalist, and now Beamon’s teammate and coach -- was the one who explained to him what he’d done.

“You really put it all together,” Boston said to him as he explained he’d gone 29’2½”.

I said the jump was staggering. On learning how far he’d gone, Beamon himself actually staggered, falling dramatically to the track as he was momentarily overcome with emotion.

Sure, there was wind and altitude in Mexico City. But Beamon still jumped two-and-a-half feet farther than anyone else would at those games. And even though his record was eventually topped in 1991 by Mike Powell (who went two inches farther), Beamon’s leap nonetheless remains atop most lists as the most stunning moment in sports history.

Watching Salute and thinking about how incredibly tense the world and the U.S. was during that incredible year of 1968, then moving over to the YouTube clips of Beamon, I couldn’t help but formulate a vague thesis that some of Beamon’s extra adrenaline had come from the charged atmosphere surrounding him as he leapt through the air.

I guess both the story of Smith, Carlos, and Norman as well as that of Beamon’s leap highlight ideas about human achievement and how it is possible for us to do things we might believe are beyond our capabilities.

Labels: *shots in the dark, Bob Beamon, John Carlos, olympics, Peter Norman, Salute, Tommie Smith

, then Stojanovic three-bet big to 70,000 with

, then Stojanovic three-bet big to 70,000 with

and O’Brien called.

and O’Brien called.

, giving O’Brien top pair and Stojanovic a gutshot to Broadway. With 142,000 in the middle, Stojanovic led with a huge overbet of 160,000. O’Brien paused at that for a short while, then called, and the pair watch the turn bring a cliché of a “blank card,” the

, giving O’Brien top pair and Stojanovic a gutshot to Broadway. With 142,000 in the middle, Stojanovic led with a huge overbet of 160,000. O’Brien paused at that for a short while, then called, and the pair watch the turn bring a cliché of a “blank card,” the  .

.