More on Moneyball

I was writing last Friday about having picked up Moneyball by Michael Lewis, the 2003 book in which Lewis engagingly discusses changing attitudes toward the evaluation of talent in baseball, focusing largely on the ahead-of-the-curve thinking and decisions made by the Oakland A’s during the late 1990s and early 2000s.

I was writing last Friday about having picked up Moneyball by Michael Lewis, the 2003 book in which Lewis engagingly discusses changing attitudes toward the evaluation of talent in baseball, focusing largely on the ahead-of-the-curve thinking and decisions made by the Oakland A’s during the late 1990s and early 2000s.Last week I was recommending the book to poker players, mentioning just a few ways observations shared in the book tended to overlap with issues and strategy we often associate with poker. I quoted a passage appearing early on characterizing the “old school” of talent evaluation in baseball and pointed out some obvious parallels to poker.

Having now finished Moneyball, I’m looking back at many other passages illustrating all sorts of different connections with poker. Now and then Lewis explicitly evokes gambling and casino games -- and even poker a couple of times -- such as when he characterizes the non-method method employed by many baseball teams when it comes to drafting players. Time and time again, teams with bad records (who thus get to draft early) squander their picks on high school players who more often than not won’t pan out as big leaguers.

Lewis characterizes such high-risk plays thusly: “The worst teams in baseball, the teams that can least afford for their draft to go wrong, have walked into the casino, ignored the odds, and made straight for the craps tables.” Meanwhile the Oakland A’s brain trust don’t “think of the draft as a crapshoot” but operate more like “card counters at the blackjack tables.”

That said, there isn’t a lot of specific reference to poker or gambling games in the book. But the parallels are everywhere.

Reading on the Kindle allows you to highlight passages just by running a finger over them. Then later you can go back and look only at those passages (in a folder called “My Clippings”). I kind of went overboard with the highlighting with Moneyball, actually. But I’ve spent a little time sifting through my “clippings” from the book in order to organize them under six poker-related headings I thought I’d share here.

Again, take all this as a general recommendation of the book as well as an implicit argument about the many ways poker and baseball are alike.

The Mental Game

A running theme in the book concerns how baseball requires mental toughness in addition to physical ability.

A running theme in the book concerns how baseball requires mental toughness in addition to physical ability. Oakland general manager Billy Beane’s playing career sounds as though it was cut short considerably thanks to his being unable to control his emotions and not avoid going on “tilt” after things didn’t go his way. “Emotions were always such a big part of whatever he did,” says Lewis. “A bad at bat or two and he was done for the third and fourth at bats of the game.”

A contrast is drawn between Beane and Lenny Dykstra, the Phillies star who perhaps wasn’t as physically gifted as Beane but had a significant mental edge. “Lenny didn’t let his mind screw him up,” writes Lewis. “The physical gifts required to play pro ball were, in some ways, less extraordinary than the mental ones.”

In fact, Lewis speculates that Beane’s fascination with “sabermetrics” and new ways of analyzing the game and evaluating talent stems in large part from his mental struggles as a player. “Beane tilts easily,” Lewis writes, “kind of an explanation for/cause of his fascination with ‘objective’ evidence.”

Being Results-Oriented

Speaking of the “mental game,” relatively early on Lewis quotes a psychologist named Harvey Dorfman who authored a book called The Mental Game of Baseball. Dorfman actually worked for the A’s at one point prior to Beane’s tenure there. Among other observations, Dorfman makes one about the type of player who “‘sees himself exclusively in his statistics. If his stats are bad, he has zero self-worth.’”

Speaking of the “mental game,” relatively early on Lewis quotes a psychologist named Harvey Dorfman who authored a book called The Mental Game of Baseball. Dorfman actually worked for the A’s at one point prior to Beane’s tenure there. Among other observations, Dorfman makes one about the type of player who “‘sees himself exclusively in his statistics. If his stats are bad, he has zero self-worth.’”Of course, in baseball it isn’t just players letting their numbers influence their ideas of themselves. Those in charge of evaluating talent and trading for or signing players are also heavily swayed by such numbers, and thus let results (i.e., players’ stats) affect their decisions. That’s not necessarily a problem in and of itself; however, it can be a big one if the stats are being misinterpreted.

For example, Bill James (featured heavily in Moneyball, especially during the first half) is quoted at one point complaining way back in the 1980s about how batting average gets overvalued in baseball. “‘I find it remarkable that, in listing offenses, the league will list first -- meaning best -- not the team which scored the most runs, but the team with the highest batting average’” says James. “‘It should be obvious that the purpose of an offense is not to compile a high batting average.’”

Thus did James come up with a new stat -- “runs created” -- that was a better indicator of a player’s offensive worth. Others followed James to come up with still more ways to isolate skill from luck in baseball, and while I won’t bore you with all of the examples I will say all tend to challenge traditional measures of achievement by focusing more on players’ ability to perform in ways that maximize the team’s chance of success.

As Paul DePodesta, Beane’s assistant, puts it: “‘It’s looking at processes rather than outcomes.... Too many people make decisions based on outcomes rather than processes.’”

It is perhaps easier in poker than in baseball to distinguish processes from outcomes. We can often tell when we’ve played a hand well yet gotten unlucky, or played a hand badly but managed to hit a two-outer and win anyway. What we do with that knowledge, though, is what makes us better or worse poker players.

Appearances

Innovations introduced by the Oakland A’s regarding drafting players, organizing rosters and line-ups, and in-game decisions looked weird to those unfamiliar with the underlying reasoning. But the A’s staff didn’t care, and the book kind of promotes those guys as fearless iconoclasts often unfazed by criticisms of those unaware of the method behind their seeming madness.

Innovations introduced by the Oakland A’s regarding drafting players, organizing rosters and line-ups, and in-game decisions looked weird to those unfamiliar with the underlying reasoning. But the A’s staff didn’t care, and the book kind of promotes those guys as fearless iconoclasts often unfazed by criticisms of those unaware of the method behind their seeming madness.A good example of the lack of care about appearances is the shunning of “textbook” baseball plays like moving a runner over with a sacrifice bunt, stealing bases, or using the hit and run. “Bunts, stolen bases, hit and runs -- they all were mostly self-defeating and all had a common theme: fear of public humiliation,” Lewis explains. He then quotes Pete Palmer, an engineer-turned-sabermetrician, pointing out how “‘Managers tend to pick a strategy that is least likely to fail rather than pick a strategy that is most efficient.... The pain of looking bad is worse than the gain of making the best move.’”

Poker presents us with similar spots quite often, where we avoid making a play that is in fact correct out of fear that it may look strange or incorrect to others. Particularly when it comes to unorthodox or “innovative” plays that go against “received wisdom,” some of us might in such cases resist making what we know is the best move.

Under this heading I’ll also put the extreme emphasis on drawing walks that is part of the “moneyball” strategy. Reading about the reasons why walks should be valued frequently made me think about folding in poker, another action that is perhaps undervalued by some because of how it looks -- surrendering, not fighting, and thus appearing weak.

But such patience reaps great rewards both in baseball and in poker. As Lewis explains, “Any ball out of the strike zone was an opportunity for the batter to shift the odds in his favor. All you had to do was: not swing!”

Game Theory

Specific discussion of game theory comes up now and then in Moneyball, and again the potential application to poker is obvious. A lot of times the idea arises when talking about the confrontation between pitcher and batter, a duel that in many ways resembles a heads-up situation in poker.

Specific discussion of game theory comes up now and then in Moneyball, and again the potential application to poker is obvious. A lot of times the idea arises when talking about the confrontation between pitcher and batter, a duel that in many ways resembles a heads-up situation in poker.A reader taxdood commented on that earlier post and mentioned the great description of an at-bat between Oakland first baseman Scott Hatteberg and Jamie Moyer, both of whom might be described as above-average when it comes to using game theory to try to “level” opponents. It’s a great scene, with Lewis doing a neat job describing the head games going on between the two.

I love the moment near the end of the at-bat when Moyer steps off the mound and says directly to Hatteberg “‘Just tell me what you want.’” Hatteberg has no response to that, it being unprecedented for a pitcher to ask directly what pitch and/or location he desires. Such a tactic reminded me of the poker player asking an opponent if he or she wants him to call or fold, or similarly direct queries that can play an important role in how the game is played.

I also like how Hatteberg describes someone like Moyer in terms that might remind us of a very savvy poker player who is able to flummox opponents with clever, hard-to-decipher betting patterns. “A good pitcher... creates a kind of parallel universe,” explains Hatteberg. “It doesn’t matter how hard he throws, in absolute terms, so long as he is able to distort the perception of the hitters.” The sort of thing can make players make mistakes, in baseball and in poker.

(Hatteberg is described elsewhere as loving to chat up opponents reaching first base, something Lewis explicitly suggests is “like chatting at the poker table.”)

Meanwhile you have those in baseball who like inexperienced poker players are oblivious to “leveling” or other “game theory”-type tactics. As another player, John Mabry, points out, “‘Some of the guys who are the best are the dumbest.... I don’t mean the dumbest. I mean they don’t have a thought. No system.... Guys can’t set you up. You have no pattern. You can’t even remember your last at bat.’”

Playing by the Numbers vs. Playing by “Feel”

The debate explored in the book between the old way of looking at baseball and the new -- what Lewis in a postscript refers to as “baseball’s religious war” -- breaks down in various ways, but one way of characterizing it is a conflict between “faith”-like, instinctive responses unconfirmed by concrete evidence running up against cold, rational facts.

The debate explored in the book between the old way of looking at baseball and the new -- what Lewis in a postscript refers to as “baseball’s religious war” -- breaks down in various ways, but one way of characterizing it is a conflict between “faith”-like, instinctive responses unconfirmed by concrete evidence running up against cold, rational facts.“In human behavior there was always uncertainty and risk,” says Lewis. “The goal of the Oakland front office was simply to minimize the risk. Their solution wasn’t perfect, it was just better than the hoary alternative, rendering decisions by gut feeling.”

Such passages make me think of arguments raised by some against those getting too carried away with letting ideas about the math of poker overwhelm other ways of looking at the game. Obviously you want to try to find a good balance between the numbers and “feel,” but it sounds like in baseball there has existed (and perhaps still exists) a strong, influential majority in charge of running teams who have essentially done it by “feel” alone for many, many years.

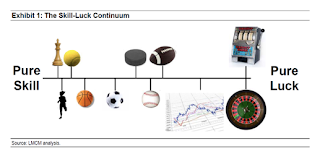

Luck vs. Skill

There is so much in Moneyball concerning the relative balance of luck and skill in baseball, I’m going to cut short summarizing the references if only to keep this post from getting any longer than it already is.

There is so much in Moneyball concerning the relative balance of luck and skill in baseball, I’m going to cut short summarizing the references if only to keep this post from getting any longer than it already is. I talked about one instance in a “Pop Poker” piece for PokerListings this week, if you’re curious. The article is called “On Luck, Skill, Hail Marys and Moneyball,” and brings up one example of pitchers “running good” when it comes to balls being put in play and resulting in outs rather than hits.

At one point Lewis quotes another sabermetrician (Pete Palmer) estimating that “the average difference in baseball due to skill is about one run a game, while the average difference due to luck is about four runs a game.” If true, that sounds like luck holds a lot more sway in a given game than it does in, say, a session of poker, doesn’t it?

I’ll refer to one other interesting example of luck in baseball -- the postseason, which Lewis refers to as “a giant crapshoot” in which luck really does affect outcomes greatly and thus can “frustrate rational management because, unlike the long regular season, they [the playoffs] suffer from the sample size problem.”

That characterization of the relationship between the playoffs to the regular season in baseball makes me think of final tables in poker tournaments where it sometimes happens that after hours (or days) of skill mattering more than luck, the blinds have risen to a point where luck predominates. In other words, at the most crucial moment when ultimate winners and losers are determined, the game

becomes “a crapshoot.”

There are many other gems in the book I might’ve included here, including what I consider a highly persuasive argument on behalf of the importance of studying or writing about baseball. That is to say, Lewis (along with many of those whom he talks to or quotes) does a good job justifying his object of inquiry being worthwhile, and does so in ways that remind me why poker is also “more than just a game” and thus similarly worth studying and writing about.

But I’ll stop here and let those of you who haven’t read Moneyball go check it out for yourselves. Or for those who have read it, I’ll invite you perhaps go back and check it out again with an eye toward all of the many ways the story and its characters speak to poker players.

Labels: *by the book, Michael Lewis, Moneyball

Jesse May (Shut Up and Deal) returns this week with another episode of his podcast, “The Poker Show.” It’s been about six weeks since May’s last show back in early July (near the end of the WSOP), making the appearance of a new one notable.

Jesse May (Shut Up and Deal) returns this week with another episode of his podcast, “The Poker Show.” It’s been about six weeks since May’s last show back in early July (near the end of the WSOP), making the appearance of a new one notable.

. Selbst had

. Selbst had

for sevens and fives, while Lamb had

for sevens and fives, while Lamb had

for a spade flush. Thus when we watch on ESPN we see that Selbst forced Lamb to fold the best hand.

for a spade flush. Thus when we watch on ESPN we see that Selbst forced Lamb to fold the best hand.