The Shape of the World

When I first heard the story a few days ago, I thought perhaps it was a prank of some sort being pulled by Irving, meant to illustrate how outrageously easy it is to manipulate social media, which in turn makes it trivially simple to make any sort of absurdity go “viral.” After all, if you had thought about it a week ago, the idea that Kyrie Irving believes the earth is flat probably would have seemed almost as unlikely as the earth actually being flat.

But, no. He wasn’t joking. Given that Irving spent part of a year at Duke University before going pro provides this UNC fan a ready opening, of course. But I’m more interested in a larger issue connected to this story.

Irving made his position known on an episode of a podcast hosted by two of his Cleveland teammates, Richard Jefferson and Channing Frye. Amid talk of conspiracy theories, Irving mentioned his view about the planet’s shape, defending it as not a conspiracy but a fact (in his estimation). “If you really think about it from a landscape of the way we travel,” Irving explained, “the way we move... can you really think of us rotating around the sun, and all planets align, rotating in specific dates...?”

There’s more, but it’s hardly worth transcribing. The gist of his position is to insist that “there’s a falseness in stories and things that people want you to believe and ultimately what they throw in front of us.” Or, to put it another way, “I think people should do their own research, man.”

Some, like NBA Commissioner Adam Silver, shared my initial, skeptical response to the story of Irving’s skepticism and tried to contextualize Irving’s comment in a way that made it seem less patently ignorant. “He was trying to be provocative and it was effective,” Silver said, reflecting on Irving’s own later comments about the furor he’d created.

“I think it was a larger comment on the sort of fake news debate that’s going on right now... and it led to a larger discussion,” added Silver, who didn’t omit appending the sanity-affirming disclaimer “I personally believe the world is round.”

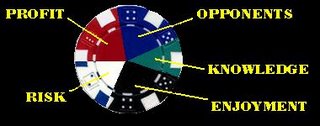

The denial of objective truth is difficult to combat. It’s quite challenging to convince a superstitious poker player who refuses to accept that the cards dealt on one hand are wholly independent of the cards next on the next one that the “pattern” he perceives is in truth wholly subjective and not at all meaningful. You have to find some sort of common ground even to communicate with someone refusing to accept something as fundamentally obvious as the planet’s shape, rotation, and orbital path.

Existentialism encourages us to make our meaning, emphasizing subjective experience over the blind acceptance of received ideas about “reality” -- that is, not to receive “what they throw in front of us” without applying a little of our own rational analysis as a test. That doesn’t preclude, however, accepting certain (nominally) objective truths, even tentatively. Like, say, the laws of physics.

If Irving really understood the science, he’d understand how gravity works, which explains why when he launches a basketball skyward it comes back down toward the spherical planet’s center and doesn’t careen toward the center of his imagined “flat” earth, wherever that might be (one of dozens of easy-to-observe phenomena proving the earth’s roundness). Irving apparently hasn’t considered this or if he has he doesn’t find convincing the evidence he necessarily witnesses every waking moment of his life.

Silver -- who probably doesn’t care too much about one of the league’s stars espousing what might be called “fake science” -- grabs that “fake news” thread, trying to suggest that Irving was himself making some sort of point about the need to be skeptical amid what can certainly be a confusing climate of reporting and news-sharing.

But that kind of twists what Irving was saying. Rather, he was only referring to his incredulity that people would care so damn much about his position that the earth is flat.

“There are so many real things going on, actual, like, things that are going on that’s changing the shape, the way of our lives,” Irving told ESPN a couple of days after the initial blast. In other words, he doesn’t view the news of his belief as being “real” or “actual” (as in “significant”) compared to other, more important issues.

Irving even unwittingly puns on the word “shape,” saying (to paraphrase) that we should concern ourselves much more with the things certain people are currently doing to shape our world in a figurative sense than with the literal shape he imagines the world to be.

I agree with Irving on that point. In other words, I’m glad to know that our perspectives regarding the world in which we both live overlap at least in this way. I’m also more worried about the “things going on that’s changing the shape” of our world -- particularly about the people who are doing those “things” -- than about Irving’s flat-earth folly.

I’m additionally concerned, though, when the people shaping our world seem influenced by ideas about it that are easily discovered to be false.

Need examples? People can do their own research, man.

Image: “Fragile Planet,” Dave Ginsberg. CC BY 2.0.

Labels: *the rumble, Adam Silver, existentialism, fake news, Gravity, Kyrie Irving, NBA, physics

-- a decent flop for me, one would think. I bet and both of my opponents called. $6.25 in the pot. The turn was the

-- a decent flop for me, one would think. I bet and both of my opponents called. $6.25 in the pot. The turn was the  and I actually checked. To be perfectly honest, my memory is a little foggy here as to why I checked. In fact, when I looked back at the hand in

and I actually checked. To be perfectly honest, my memory is a little foggy here as to why I checked. In fact, when I looked back at the hand in  , making the board

, making the board

. UTG+1 had

. UTG+1 had

, winning the $10.25 pot (minus $0.45 for the rake) with his ace kicker to the two pair on the board.

, winning the $10.25 pot (minus $0.45 for the rake) with his ace kicker to the two pair on the board.