Play the Game Existence to the End of the Beginning

“Back to quits” is one of my favorite poker expressions, although I don’t think it is one that is all that commonly known or used. I don’t see it in The Official Dictionary Poker by Michael Weisenberg, accessible online over at Mike Caro’s site. Nor does it appear in The Poker Encyclopedia compiled by Ethan Allan and Hannah Mackay.

“Back to quits” is one of my favorite poker expressions, although I don’t think it is one that is all that commonly known or used. I don’t see it in The Official Dictionary Poker by Michael Weisenberg, accessible online over at Mike Caro’s site. Nor does it appear in The Poker Encyclopedia compiled by Ethan Allan and Hannah Mackay.Can’t recall exactly where I first encountered it. I know Anthony Holden uses the phrase in Big Deal, which is why I think of it as probably more of a British term -- like calling a player a “punter” or the pot the “pool.” Early in the book, Holden describes starting out his year-long experiment as a poker professional with some losses, followed by a couple of cashes in small tourneys and “a run of cards in a £5-and-£10 Hold ’Em side game, which got my bankroll back to quits.”

The meaning of the phrase is clear enough, I assume -- getting back to even. I like the way the phrase connotes that irrational feeling we’ve all had that makes recovering one’s starting stack a requirement for leaving the game.

We know it’s wrong to think this way. “Perhaps the stupidest words in poker are ‘I’ve got to get even,” writes Al Schoonmaker in Your Worst Poker Enemy. “When you feel that way, you are in danger of turning an unpleasant loss into a catastrophe,” explains the psychologist. “You can get further off balance, play more poorly or perhaps go to a larger game or the craps table, desperately trying to get even.”

Thus do I like calling it getting “back to quits” rather than getting even, because the phrase tends to remind me that my real goal is simply to leave the game -- which perhaps I should consider going ahead and doing rather than pressuring myself to recoup my losses. In other words, realizing that I’m simply trying to get “back to quits” sometimes helps me get up from the table sooner -- not always easy to do. (Wrote about that a couple of times before, actually, in “Poker Sisyphean Challenge” and “The Long Goodbye”).

I sometimes marvel at how this mindfulness of how much I am up or down perfectly evokes the existentialist idea of “making meaning” -- in this case, interpreting the meaning of my play according to what is necessarily a wholly subjective criterion that only really matters to me. In fact, depending on how aware my opponents are, sometimes I might be the only one who even knows if I’m up or down. And even if others are aware, they haven’t a true idea what the significance of being up or down (by a lot or a little) means to me, anyway.

It was during another session of Rush Poker (pot-limit Omaha, six-handed, $25 buy-in) that I found myself thinking about all of these things once again. Despite playing a few hands well early on, I’d taken a couple of unfortunate beats, then made a couple of missteps to take me nearly two buy-ins down. I gradually fought back, and without winning any large pots managed to get almost “back to quits” before signing off.

As those who have played Rush Poker know, with each new hand you are taken to a new table. After a while, you do start to see the same players, and it is even possible to get reads and use them (especially if you are a note-taker). But a lot of what happens in each individual hand happens without the usual contextual info of the standard game.

I realized absolutely no one knew whether I was up or down during my session. In fact, towards the end I was sitting with a fairly big stack (nearly three buy-ins deep), but was still down a couple of bucks. Nor did anyone know if I’d been playing well or poorly.

A hand came up where it folded to me on the button and I raised pot with a trash hand. As I did, I momentarily thought of my “image” and its significance (or lack thereof). My opponents didn’t really know if I was the sort of player who sometimes would raise with bad cards there. But I did.

As I waited for the blinds to act, I began involuntarily thinking about how I’d played the last couple of times it had folded to me on the button, actually considering -- and maybe even being slightly affected by -- the patterns in my own play. Patterns I had noticed, but no one else had.

The existentialist recognizes that while we play with each other, what the game means is necessarily going to be different to each of the players. And if for you getting to the end means returning to the beginning, well, only you may see the meaning of within.

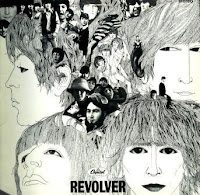

Labels: *shots in the dark, Al Schoonmaker, existentialism, Rush Poker, The Beatles

3 Comments:

are you sure back to quits can't go the other way ... like you are winning, and suddenly you aren't, and before you know it, you have run out of money and therefore are "back to quits"?

Back to quits makes sense but it's not a phrase used much on this side of the pond.Double or quits is far more common.( usually after losing a prop bet with a friend)

Thx, Littleacornman. I haven't seen the phrase used that way, Dan -- always seems to refer to digging back out of a hole. Does sound like an alternative (and more literal) usage, though.

Post a Comment

<< Home