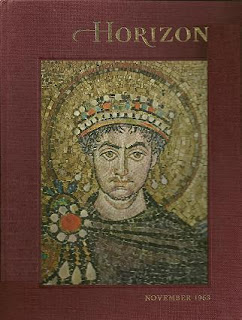

“Poker and American Character” by John Lukacs (November 1963) (2 of 2)

Continuing today with my review of an interesting essay about poker appearing in 1963 in a scholarly journal called Horizon. The article is by the historian John Lukacs who grew up in Hungary loving poker, then moved to the U.S. following World War II. In the 17 years since the move, Lukacs had become a bit disenchanted with the development of poker here in its country of origin. (If you missed it, here is the first part of the discussion.)

Continuing today with my review of an interesting essay about poker appearing in 1963 in a scholarly journal called Horizon. The article is by the historian John Lukacs who grew up in Hungary loving poker, then moved to the U.S. following World War II. In the 17 years since the move, Lukacs had become a bit disenchanted with the development of poker here in its country of origin. (If you missed it, here is the first part of the discussion.)We left off with Lukacs’ complaints about all games other than what he calls “classic” poker, namely those variations of poker that in his view tend to increase the chance element, making it more of a gambling game and minimizing the “psychological factors” which otherwise make poker different from (and better than) most games.

For Lukacs “classic” poker begins and ends with draw poker, and thus he speaks with equal disdain for Spit in the Ocean as he does for seven-card stud high-low. Noting how these other variations have appeared to take over in mid-20th century America, Lukacs says the “golden age of poker in the United States seems to have been from 1870 to 1920,” at which point poker’s decline began for the historian.

Women in Poker

Lukacs also isn’t happy about other developments having occurred in poker in the U.S. by the time he arrived in the country, including women starting to be allowed into the games. “This [women playing poker] began around 1920, after the Constitutional amendment ordering female suffrage” was passed. That is also when women smoking in public began to be accepted, too, something else Lukacs ain’t too crazy about.

Lukacs also isn’t happy about other developments having occurred in poker in the U.S. by the time he arrived in the country, including women starting to be allowed into the games. “This [women playing poker] began around 1920, after the Constitutional amendment ordering female suffrage” was passed. That is also when women smoking in public began to be accepted, too, something else Lukacs ain’t too crazy about.“I believe that this wide introduction of the female element diluted the character of poker (just as Prohibition led, however indirectly, to the dilution of spirits)” argues Lukacs. Why is he of that opinion? “Women are notoriously bad gamblers,” he explains. “They find it difficult to exclude social considerations from a game that must be organized around a social occasion.” It sounds like he’s saying women are too easily distracted by the special form of socializing associated with poker, a game which he says possesses “strongly masculine characteristics.”

We recall Lukacs writes in the early 1960s, a time when such attitudes about women and even the freestyle gendering of a card game as “masculine” could often pass without being questioned. (How exactly is poker “masculine?” we might jump to ask today.) Even so, it’s easy enough to see how Lukacs’ desire to preserve “classic” poker fits with his backing of other traditions, including conventions associated with “traditional” ideas about men and women (and their not being equal).

The Erosion of the American National Character

Ultimately Lukacs ties the decline of poker to what he calls “the erosion of the American national character.” It’s a complicated, not entirely obvious point he’s making, so let me allow Lukacs to make it himself rather than try to summarize:

Ultimately Lukacs ties the decline of poker to what he calls “the erosion of the American national character.” It’s a complicated, not entirely obvious point he’s making, so let me allow Lukacs to make it himself rather than try to summarize:“The deterioration of poker, I believe, corresponds very closely to a tendency in modern American life that I find most disturbing and dangerous: the inflation (meaning the increasing worthlessness) of words -- more menacing, even, than the inflation of money. Seven-card stud poker represents a gross inflation of values. It corresponds to the development of a society where everybody goes to college until the value of the college degree is less than that of a high-school degree forty years ago; where everybody nominally owns a house but with less of a sense of permanence and privacy than the owner of a family flat in a Naples tenement; where the Great American Novel of The Generation is published at least twice, and of Our Decade at least five times, a year; and where everybody calls everybody else by their first name.”

While we might object to Lukacs’ characterization of seven-card stud (does he really understand the game?), I think we can see the general point he’s trying to make about American “values” having changed in a troubling way. Lukacs sees this overall “inflation of values” occurring everywhere -- too much reward, not enough work -- and wants to draw an analogy between that trend and the favoring of poker games in which chance is more important than skill.

“Depending on cards rather than one’s own judgment reflects, too, a deterioration of self-confidence,” says Lukacs, further clarifying what he means by that claim about the “erosion” of the American character. “It also represents a form of immaturity, a strange kind of grown-up disorderliness covering up what is fundamentally an adolescent attitude.”

I think Lukacs may well be onto something here when he associates a love of gambling with immaturity, and tries to promote “classic” poker as a “grown-up” game that demonstrates an appreciation of order, custom, and intellectual rigor (even if he’s way too quick to reject seven-card stud high-low as a game with too much gambling.)

The “Scientification” of Poker

One other point made by Lukacs in his essay comes out of the Cold War context in which he’s writing, an observation about the application of game theory to poker. Noting the rapid emergence of government-supported research into game theory, Lukacs is very critical of “this relatively recent American passion... for intellectualizing everything, from business to military strategy.”

One other point made by Lukacs in his essay comes out of the Cold War context in which he’s writing, an observation about the application of game theory to poker. Noting the rapid emergence of government-supported research into game theory, Lukacs is very critical of “this relatively recent American passion... for intellectualizing everything, from business to military strategy.” And Lukacs hates, hates, hates what all this talk about probability and games has done to his beloved poker. “Thus, while on the one hand the playing of poker becomes perverted” by all of the crazy, gambling-centric variations, “on the other hand poker is given an elaborate theory and becomes an object of study -- insufficient seriousness on one end, and overseriousness on the other.”

Making reference to game theory pioneers Oskar Morgenstern and John von Neumann (authors of the 1944 work Theory of Games and Economic Behavior), Lukacs ends his article with a kind of tirade against the intrusion of game theory into poker.

He raises two primary objections here. One is that when talking about poker the game theorists (in his opinion) tend to assume “that all players are of the same temperament,” which is of course untrue.

The other objection is that -- here Lukacs quotes from John McDonald’s famous 1948 book Strategy in Poker, Business, and War -- “‘the theory of games... is based on the assumption that man seeks gain.’” Lukacs points out that when it comes to poker, many people in fact play for reasons other than to profit. “I have yet to see the man, except for the professional cardsharp, who plays poker primarily because he seeks gain. He plays for fun; and he hopes to make some gain.”

Lukacs then concludes with some more discussion of the Cold War and how poker could be said to have informed U.S. strategy while chess informed that of the Soviet Union. And in this context, Lukacs much favors the former. “Poker is a unique game because is approximates life,” says Lukacs. “That is not true of chess, which is circumscribed by a framework of mathematical rules and is therefore irrevocably artificial.”

That’s the view that causes Lukacs to reject attempts at the “scientification” of poker. He notes more than once along the way that one could never play poker against an IBM machine (the way one can play chess). That human element -- the “psychological factors” -- just cannot be replicated by a computer, says the historian.

All in all a very interesting and provocative piece, I thought, that gives the reader a good idea of poker’s place in American culture in the early 1960s -- that is, prior to the advent of the WSOP, the rise of Texas hold’em, and all of the other developments of the late 20th/early 21st centuries which have occurred to affect the game so greatly.

Labels: *the rumble, artificial intelligence, chess, John Lukacs

. I wanted to see a flop cheaply, if possible, so I limped in for a quarter. It folded to the button who raised pot to $1.10. The small blind folded, the big blind called, and I called as well. That made the pot $3.40 going to the flop. I had just $8.90 left -- an SPR of a little over 2.6. The flop then came

. I wanted to see a flop cheaply, if possible, so I limped in for a quarter. It folded to the button who raised pot to $1.10. The small blind folded, the big blind called, and I called as well. That made the pot $3.40 going to the flop. I had just $8.90 left -- an SPR of a little over 2.6. The flop then came

, giving me a straight.

, giving me a straight.  , I bet my last $5.50, and the button quickly called, showing

, I bet my last $5.50, and the button quickly called, showing

(not a hand I’d be too excited about even from late position in PLO). I suppose he might’ve thought the deuce gave him more straight outs, though those were no good. The river brought the

(not a hand I’d be too excited about even from late position in PLO). I suppose he might’ve thought the deuce gave him more straight outs, though those were no good. The river brought the  , and my hand had held up.

, and my hand had held up.

, Maurer in the big blind with

, Maurer in the big blind with

, and Carr on the button with

, and Carr on the button with

, and all three players make straights on the turn, with the board showing

, and all three players make straights on the turn, with the board showing

, pairing the board, and Maurer wastes little time moving all in for his last 8,925. Carr doesn’t wait long, either, before calling, and Matusow is a bit dismayed to see his two opponents had neither better straights, flushes, or full houses.

, pairing the board, and Maurer wastes little time moving all in for his last 8,925. Carr doesn’t wait long, either, before calling, and Matusow is a bit dismayed to see his two opponents had neither better straights, flushes, or full houses.

on the button. The cutoff limped in for a quarter, and I raised to $1.00. The small blind folded, then both the big blind and the cutoff called.

on the button. The cutoff limped in for a quarter, and I raised to $1.00. The small blind folded, then both the big blind and the cutoff called.

. (I said I’ve been running good.) I get top set, with no flush draws to fret (yet). It checked to me, I bet $1.75, and only the big blind stuck around. Pot now $6.60.

. (I said I’ve been running good.) I get top set, with no flush draws to fret (yet). It checked to me, I bet $1.75, and only the big blind stuck around. Pot now $6.60.  . Not too worried about a set of aces here, and now I have the nut flush draw. My opponent, now with $13.21 left, checked, and I went ahead and made a nearly pot-sized bet of $6. His quick call made me think he’d either picked up a diamond draw, too, or perhaps had flopped a set of sixes or deuces. Pot up to $18.60.

. Not too worried about a set of aces here, and now I have the nut flush draw. My opponent, now with $13.21 left, checked, and I went ahead and made a nearly pot-sized bet of $6. His quick call made me think he’d either picked up a diamond draw, too, or perhaps had flopped a set of sixes or deuces. Pot up to $18.60.

. He’d flopped top-and-bottom pair and a gutshot, chased, then made a failed play on the end to try and steal the big pot.

. He’d flopped top-and-bottom pair and a gutshot, chased, then made a failed play on the end to try and steal the big pot.