It’s easy to overreact.

A new player sits down at the table and immediately starts opening every pot, consistently raising two or three times the “norm.” He’s betting and raising after the flop, too, instantly disrupting the game’s previous rhythm and causing a kind of temporary paralysis to take over many players at the table.

He’s kind of a jerk as well, it turns out, making rude comments to the dealer and wait staff, and even directing a few unfriendly, terse judgments toward others at the table.

You gradually start to adjust to this newcomer -- or to tell yourself you’re adjusting, even if you’re still folding every hand to his raises while keeping mum. “I’ll find a spot,” you think to yourself, convinced this new, reckless-appearing style can’t possibly be effective over the long term.

Since the inauguration a week-and-a-half ago, the president of the United States and his team of advisors have heightened fears among many that his tenure in office will create lasting damage to the nation’s welfare and standing in the global community. Whether they will succeed in transforming the country’s core values -- equality, liberty, individualism, justice, the common good, diversity and unity -- is less certain, although those, too, are obviously under siege.

Indeed, through a hastily delivered series of executive orders and presidential memoranda, numerous erratic and hair-raising statements (including threats) by himself and his team to various groups including the press, and the continued advancement of an overall impression of instability and startling unpredictability, it appears damage has already been done that will take many years and likely multiple subsequent administrations to repair.

Unlike at any other time I can remember -- save, perhaps, the days following the attacks of 9/11 -- the country and its organizing principles feel genuinely threatened. Every single day since January 20 has presented new evidence to suggest that life as we know it both here in the U.S. and elsewhere is swiftly transforming into something less certain and more potentially destructive. Those among us who are not overtly supportive of the president and his team will suffer the most and the most directly, although even many of the most ardent red hat-wearers are going to find themselves significantly hurt as well.

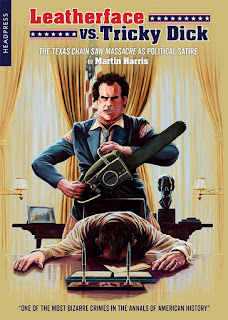

Many commentators have suggested a few analogies between the present administration’s wrecking ball approach to governance and the damage inflicted during the five-and-a-half years of Richard Nixon’s presidency. It’s a logical step to make, given that there are some parallels. It’s also kind of an assuring one, in a way, suggesting as it does (at least indirectly) that what is happening right now isn’t necessarily as bad as it seems since, well, the world didn’t end with Nixon.

That’s what a friend of mine was telling me just last Friday after I commented to him how “exhausting” it was following the coverage of yet another crisis or three having been introduced by this administration. I brought up to him Nixon’s famous “Saturday Night Massacre,” that remarkable, turning-point moment in the Watergate scandal when the president’s willingness to abuse his power became much clearer to many and the idea of impeachment became a lot more concrete.

In May 1973, Nixon had his Attorney General Elliot Richardson appoint a Watergate Special Prosecutor to investigate improprieties related to the ’72 election, and Richardson appointed Archibald Cox. In fact Richardson had only been made A.G. immediately before making the appointment, and during his confirmation hearings had assured the Senate he wouldn’t use his authority to dismiss Cox without there being sufficient cause to do so.

In July came the public revelation of the White House taping system, and Cox soon was asking for copies of tapes of some of the recorded conversations about the break-in and its subsequent handling. The White House refused to hand them over, and Cox responded by serving a subpoena for the tapes. The resistance continued with Nixon continuing to refuse to hand over tapes, claiming “executive privilege.” By October Nixon and his staff came up with a compromise plan to have a senator listen to and summarize the tapes, but Cox refused to agree with such a compromise.

The next day -- Saturday, October 20, 1973 -- Nixon ordered Richardson to fire Cox. Richardson refused to do so, referring back to his promise to the Senate, and resigned in protest. Nixon then ordered the Deputy A.G. William Ruckelshaus to fire Cox, and he also refused the order and resigned. Finally the next in line, Soliticor General Robert Bork, did fire Cox.

News coverage of that night is interesting to follow, and gives a sense of just how strange and scary it all seemed at the time. There is two hours’ worth of audio that compiles TV networks’ reporting from that evening and just afterward

available over on archive.org. You hear anchors breathlessly describing the developments as “stunning” and “dramatic” and “unprecedented,” with talk of a constitutional crisis like nothing they had ever witnessed before.

To my friend I remarked that every single day last week felt like what those anchors were describing when reporting on the Saturday Night Massacre. It began with the president’s dark, divisive inauguration speech and absurdist one-man show before the CIA where his primary message concerned his “running war with the media.” Then came the feverish first performance by his press secretary in which he threatened to “hold the press accountable” while (1) strangely insisting upon statements about the inauguration crowd sizes that were verifiably false, and (2) not taking any questions himself. (It was more out there than anything Ron Ziegler ever did as Nixon’s sometimes combative and accusatory press secretary.)

The next day the Counselor to the President infamously defended “alternative facts,” helping encourage Orwellian-inspired commentaries. The various executive orders and memoranda then came raining down over the next several days (I won’t summarize all of them), fueling the fire of discontent in very deliberate-seeming ways. Finally on late Friday afternoon came the E.O. titled “Protecting the Nation from Foreign Terrorist Entry into the United States,” which suspends the U.S. Refugees Admissions Program for 120 days while also prohibiting entry into the country of anyone from seven countries, all of which have overwhelmingly Muslim populations.

Chaos and confusion followed that last one, including protests and ugly scenes at airports all over the U.S. In the days since details have surfaced regarding the non-standard procedures followed by the president and his team to produce the order, including failing to consult with administration officials and his own party’s legislators before the order was signed.

As I say, I had already been reminded of the Saturday Night Massacre a few days before. But then last night everyone was reminded of it when the current Attorney General Sally Yates chose to defy the president in a manner that somewhat echoed Richardson’s action, even if the circumstances are quite different, when issuing a directive to the Justice Department not to defend the executive order. The president swiftly fired Yates (adding -- as he cannot avoid doing whenever he does anything -- a bitter, personal social media message about her).

I wake up this morning to more headlines sounding the alarm, and I brace myself like many others are for the next threat to emerge.

The argument over “who’s worse” between Nixon and Trump is an interesting one, though perhaps of limited practical value at such an early stage.

Nixon is the past. His presidency caused significant trauma to this country, weakening both the office and the American government in serious ways. After Nixon became president and especially starting near the end of his first term in office, he explored methods to remake government entirely, in particular to increase the overall power of the executive branch either by reducing constraints upon it or by exploiting weaknesses in the system of checks and balances. He and his reelection committee additionally engaged in outright criminal activity.

The Watergate break-in and subsequent cover-up (and, as importantly, the attempted cover-up of the cover-up) would not only overwhelm Nixon’s ability to continue as president, it would obscure deeper, more significant corruption and illegality both in his campaign and his administration, not to mention the usurping of power that enabled him to order intervention in Cambodia without Congressional approval and similarly to continue the Vietnam War by evoking his title as Commander-in-Chief of the military.

However the “system” did manage to remove him from office (thanks both to some good fortune and strategic missteps by Nixon himself). And, as my friend reminded me, the country and its government did survive him.

Now this new jerk has come to the table. Some of us actually invited him. And within just a few hands it’s obvious that he is clearly doing everything he can to ruin the game. I’m reminded how I pursued this same analogy nearly a year-and-a-half ago, right after the first G.O.P. debate, in a post titled “America Is In Serious Trouble.”

Whatever his intentions might truly be, it’s clear he wants both to provoke us all and to keep us all fixated on him and him only. Eventually everything we do or say (he hopes) will necessarily be influenced by him. He’s not just playing to win, but to make it impossible for anyone else ever to win again.

Sure, it’s easy to overreact. Then again, against certain opponents whose actions are themselves wildly, crazily disproportionate, what feels like overreacting is simply responding in kind.

Images: “Trump signing order January 27” (top), Staff of the President of the United States, Public Domain; front page of the New York Times (October 21, 1973), Fair Use.

Labels: *the rumble, 2016 presidential election, Donald Trump, Richard Nixon, Watergate