Rereading The Biggest Game in Town: Playing Jimmy Chagra (4 of 6)

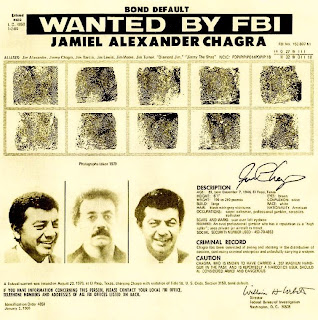

Amid discussing the seeming disregard for money exhibited by most high-stakes poker players in chapter 3 of The Biggest Game in Town, Al Alvarez briefly relates a few details of the story of Jimmy Chagra, the notorious drug trafficker who spent his last months of freedom gambling it up in Las Vegas in 1979.

Amid discussing the seeming disregard for money exhibited by most high-stakes poker players in chapter 3 of The Biggest Game in Town, Al Alvarez briefly relates a few details of the story of Jimmy Chagra, the notorious drug trafficker who spent his last months of freedom gambling it up in Las Vegas in 1979.I’ve mentioned Chagra here at least a couple of times before. After returning from covering the 2008 WSOP, I wrote a post about the coverage of the 1979 World Series of Poker in Gambling Times magazine. There I shared details of John Hill’s feature story on that year’s Series, including his reference to Chagra winning millions playing blackjack and craps during that spring’s WSOP.

Shortly after that post appeared, the author Hill came around to comment, noting that “Chagra was affable and friendly” in his recollection, “but one it would be best to put large distances between.” Hill notes how it wasn’t long after that year’s Series that Chagra would be arrested for the murder of the judge presiding over his impending trial for drug trafficking.

During the 1970s Chagra had built up a dope-dealing empire based primarily in Las Vegas and El Paso, Texas. He was finally arrested in 1978, then indicted in February 1979 on federal charges, with U.S. District Court Judge John H. Wood, Jr. of San Antonio scheduled to preside over his trial. Nicknamed “Maximum John,” Wood was known as a judge who tended to give the maximum for drug-related crimes, which for Chagra meant a possible life sentence.

On May 29, 1979 -- the day Chagra’s trial was to begin, I believe -- Wood was shot and killed outside of his home. Later it would be discovered that Chagra had hired a hit man, Charles Harrelson, to kill Wood. (Harrelson, incidentally, was the actor Woody Harrelson’s father, although he abandoned the family when Woody was still a child.)

A couple of months later Chagra would be convicted of the drug-related crimes. He’d remain a fugitive for a few months before being tracked down and imprisoned. Chagra would end up confessing to another conspiracy charge, a failed attempt to assassinate a U.S. attorney. He served until 2003 when he was freed on parole and entered the witness protection program. He died in Arizona during the summer of 2008 (coincidentally just a day after my post about the 1979 WSOP).

A couple of months later Chagra would be convicted of the drug-related crimes. He’d remain a fugitive for a few months before being tracked down and imprisoned. Chagra would end up confessing to another conspiracy charge, a failed attempt to assassinate a U.S. attorney. He served until 2003 when he was freed on parole and entered the witness protection program. He died in Arizona during the summer of 2008 (coincidentally just a day after my post about the 1979 WSOP). Chagra would actually be acquitted of the conspiracy charges to kill Wood in a trial during which Oscar Goodman, currently mayor of Las Vegas, represented Chagra as his attorney. Meanwhile Harrelson and Chagra’s brother and wife were all convicted. (Later Chagra would admit to his involvement in the conspiracy in order to try to lessen punishment for his wife.)

Obviously there’s a lot more to Chagra’s story. Author Jack Sheehan interviewed Chagra just before his death in 2008 and is working on a book while also shopping around a screenplay in Hollywood. (More on that here.)

Starting around the mid-1970s, Chagra became very well known among the high-stakes players in Vegas as a “whale” with tons of cash who loved to gamble. Indeed, in his autobiography, The Godfather of Poker, Doyle Brunson refers to Chagra as “Moby Dick.” While only an average player, he always insisted on playing for the highest stakes possible, thereby attracting the attention of Brunson and the other players who it appears even developed a kind of cautious friendship with Chagra.

During those last months in 1979, then, one imagines that Chagra was especially eager to gamble it up with the millions’ worth of criminally-derived profit he’d accrued, knowing that his days of freedom were likely numbered. Alvarez calls it his “final fling,” characterizing Chagra as viewed from the perspective of Brunson and the others as “a Platonic ideal incarnate, a high roller with no tomorrow, backed by the virtually unlimited and untaxed resources of the narcotics business.”

Arriving in Vegas a couple of years later, Alvarez asks around about how Chagra’s money got divided up among the high-stakes crowd. Unsurprisingly, no one gives up much in the way of specifics.

Arriving in Vegas a couple of years later, Alvarez asks around about how Chagra’s money got divided up among the high-stakes crowd. Unsurprisingly, no one gives up much in the way of specifics.“‘The cash got distributed pretty good’” is all he can get out of most, with Jack “Treetop” Straus adding “‘It was like that TV program Fantasy Island. I kept waiting for Tattoo to come up and say it was all a dream: “Look boss! The plane! The plane!”’”

One part of the story I’d forgotten about and found most interesting on rereading this time was how after he’d been sent away to the U.S. Penitentiary in Leavenworth, Chagra still functioned as a “whale” of sorts from within the prison walls. Alvarez talks to someone who had a friend named Travis who was also serving time in Leavenworth and who happened to be an expert gin rummy player. This fellow would stake Travis to play against Chagra, also staked from without.

“‘While everyone was reminiscing about the good old days when Jimmy was in town, I was actually playing him,’” the man explains to Alvarez. Travis won a lot initially, and payments from Chagra’s connections arrived without fail. The story ends abruptly, however, when Travis dies of a heart attack, an ending that perhaps seems more sinister than Alvarez makes it out to be thanks to the dangerous Chagra’s involvement.

Alvarez sums up the prison game as exemplifying “the imaginative coup of scoring in impossible circumstances.” Kind of punctuates the larger-than-life, mythical status Chagra possessed amid this already unreal-seeming world Alvarez was visiting.

Much like Moby Dick, Chagra was a complicated symbol -- an “inexplicable natural phenomenon” (as Alvarez characterizes Jack Binion’s references to him) -- perhaps indicating something significant about poker and gambling and how those pursuits provide a context for human ambition. As well as other, less estimable traits.

Labels: *by the book, Al Alvarez, Jimmy Chagra, The Biggest Game in Town

0 Comments:

Post a Comment

<< Home