The Flitcraft Parable

I am such a creature of habit. Almost obsessively so, I’d say.

I am such a creature of habit. Almost obsessively so, I’d say. Helps me in certain ways, for sure. While I haven’t even 1/100th of the stubborn stamina of most of these Olympic athletes I’ve been watching over the last few days, I’m pretty good at being able to focus on long-term tasks. I establish routines, stick to them doggedly, and little by little the work gets done.

Such had to have been the case for the writing of Same Difference, my hard-boiled detective novel (which you can now buy on Amazon -- check it out!).

But I’m not really talking about a trait that necessarily leads to achievement but rather a resistance to change -- a trait that likely more often than not makes it more difficult to succeed or achieve anything special.

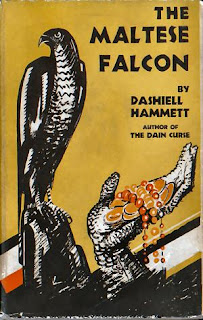

One of my favorite moments in one of my favorite novels is the so-called “Flitcraft Parable” in Dashiell Hammett’s The Maltese Falcon (1930) -- a short digression completely unrelated to the novel’s plot in which Hammett’s detective, Sam Spade, tells a little story about a man named Flitcraft. The story is often cited as illustrating that sort of “existential” or “hard-boiled” view of the world adopted by Hammett and/or Spade. It also is all about being a creature of habit who resists change.

In the story, Spade explains how Flitcraft, a real estate agent and family man living in Tacoma, one day went to lunch and never returned. Five years later his wife comes to the detective agency where Spade is working with news that someone in Spokane told her of seeing a man who looked a lot like her husband. Spade tracks him down, and sure enough, it is Flitcraft, who then explains to Spade what he’s been doing all this time.

That day he had gone to lunch, he had walked by an office building under construction, and a huge beam fell from eight to ten stories up and stunningly landed on the sidewalk next to him, nearly killing him. It had the effect of snapping Flitcraft out of his existence for a moment. “He felt like somebody had taken the lid off life and let him look at the works,” says Spade. “The life he knew was a clean orderly sane responsible affair. Now a falling beam had shown him that life was fundamentally none of these things.”

He left for Seattle that very day, then moved around a bit before eventually coming back to Washington where he again got married and started a new family. “I don't think he even knew he had settled back naturally in the same groove he had jumped out of in Tacoma,” says Spade. “But that’s the part of it I always liked. He adjusted himself to beams falling, and then no more of them fell, and he adjusted himself to them not falling.”

Like I say, the digression has nothing specifically to do with the larger plot of The Maltese Falcon, but it does loudly sound a thematic point regarding what Hammett and/or Spade had come to discover about human nature. In our efforts to find meaning in our lives, we impulsively seek certain “grooves” or patterns that tend to help us reduce our sense of uncertainty. Could be explained as a kind of survival instinct. In any case, when it comes to these routines, humans tend not to be able to get along too well without ’em.

So I guess I’m saying I’m a bit like Flitcraft. But then, we all are, to some degree.

Last April I wrote about my having this character trait in a post titled “The Ever-Present Existential Struggle With Change.” Indeed, the very fact that I’ve written about it before might be highlighted as further evidence of my “creature of habit” status.

Last April I wrote about my having this character trait in a post titled “The Ever-Present Existential Struggle With Change.” Indeed, the very fact that I’ve written about it before might be highlighted as further evidence of my “creature of habit” status. There I explained how I am one of those “who generally has a hard time changing my routine once I find something that I like or at least is comfortable enough to endure without too much hardship. That’s not to say I am not able to adapt to changes that go on around me, but rather that I myself am less inclined to introduce such changes if not forced to do so.”

A few weeks ago I sat down at a Rush Poker table on Full Tilt, playing the game I’ve been playing pretty much without exception for the last year or so, pot-limit Omaha. Had a blast at first, particularly when it seemed there were quite a few not-so-hot players occupying the other virtual seats. After while the win rate finally dropped, and the novelty wore off. My graph ended up resembling an Isildur1-like rise and fall -- speaking in relative terms, of course, and thankfully not ending in a big ugly hole like the mystery man did back in December.

(Incidentally, Isildur1 has made a return to the high stakes tables over at Full Tilt Poker, where he apparently enjoyed a $730,000 winning session yesterday, most of which came versus Justin Bonomo. Read more here.)

But even though the enjoyment had waned, I still kept going back, instinctively joining the same silly game over and again. Not so much to satisfy some junkie-like fix such as Dr. Pauly lyrically detailed in his inventive “Memoirs of a Rush Addict” post in late January. Rather, I kept returning because of this strange inertia that takes over and prevents me from looking around and finding new challenges, and encourages me to keep to the safe, familiar path.

I guess trying out the Rush Poker format in the first place was something of a change, but it wasn’t really -- I probably wouldn’t have been so willing to try it if my game (at my stakes) weren’t available. So anyhow, there I was again earlier this week, sitting at another PLO25 table, stuck a bit for the session. And stuck in a larger sense, too.

Somehow I pulled away, and went over for some limit hold’em -- a previous obsession, you could say, though a game I hadn’t really played in over a year. Remembered it well enough, and picked up enough hands to leave up a pittance. And with a smile.

A small, relatively trivial move in the grand scheme of things, to be sure. But as a creature of habit, I found it meaningful.

In that post from last April I noted how “I tend to pick one game and stick to it in an almost obsessive (or superstitious) way, even though I know switching up would likely keep my poker instincts sharper in all games.” There I am, analyzing myself pretty accurately, I’d say. Though not appearing to do too much about it.

“I also tend to have a hard time moving around stakes-wise, especially if I’m extracting a modest win rate wherever I happen to be,” I added. “Kind of limits my ever seeing what exactly I’m capable of doing, poker-wise.”

Regarding my online play, I’m going to try to find a way to start incorporating change -- that is, playing different games and trying different stakes -- as part of my routine. In other words, I’m going to try to make change familiar. Will lessen my comfort level at times, I’m sure. But overall should increase the fun, and perhaps the “achievement,” too.

I mean, if I’m gonna be stuck in some groove, I might as well try to make it groovy.

Labels: *shots in the dark, Dashiell Hammett, Dr. Pauly, Isildur1, Rush Poker, The Maltese Falcon

2 Comments:

Shamus --

Enjoyed this post -- One of my favorite aphorisms is: "A rut is a grave with both ends knocked out"

You are on the right track (I have this blog set on my side bar). Learning new games makes you a better overall player. Rush can be a problem for me also. Those big wins. Lowering stakes is also a godd offset for variance. Mixing it up can really help the bankroll.

Good Luck

Post a Comment

<< Home