ESPN finally to show the final table of the 2006 WSOP Main Event tonight. Should be interesting. Still hard to imagine playing poker for that much money . . . .

ESPN finally to show the final table of the 2006 WSOP Main Event tonight. Should be interesting. Still hard to imagine playing poker for that much money . . . .As I alluded to in the last post, I find it difficult when playing not to remain concerned about what the chips on the table actually represent. I am almost always acutely conscious of the amount I am up or down in a given session. I am certain that this awareness is one (of several) factors keeping me playing lower stakes ($0.50/$1.00, mostly). There I can play my cards and the players without fretting over the size of the pot or what my stack might look like after the hand. And knowing that I am always playing with money I have won -- I have never had to reload since that initial buy-in long ago -- makes me even more comfortable with handling whatever risks I allow myself to take.

We often hear about how players of higher stakes are somehow able to avoid such distractions and focus on the game rather than how much scratch is moving back and forth across the table. “Money means nothing,” says Chip Reese to Al Alvarez in The Biggest Game in Town. “If you really cared about it, you wouldn’t be able to sit down at a poker table and bluff off fifty thousand dollars. If I thought what that could buy me, I could not be a good player. Money is just the yardstick by which you measure your success.”

Sounds like a hopeless paradox to me. Maybe to you, too. Money means nothing, but money is the ultimate “yardstick” -- the primary means by which we evaluate our play? Of course, what sounds paradoxical to us probably doesn’t seem that way to Reese or other high stakes players. They instinctively reconcile whatever contradiction most of us see there, then put it all in with nine-high.

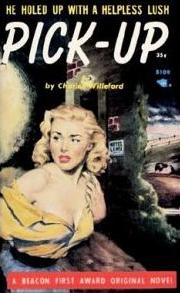

Reminds me of a passage from Charles Willeford’s 1967 novel Pick-Up. The novel is one of the most intense examples of “hard-boiled” fiction you’re going to find, rivalling Camus in its exploration of existentialist thought. I recommend the book wholeheartedly to anyone interested in the genre. Those looking for “feel-good” stories need not bother. Nor should anyone who doesn’t like to expose him or herself to graphic, emotionally-draining descriptions of violence. I won't give away much in the way of plot details here. You've got to read this one to believe it. Trust me when I say this is one of those books that once you’ve reached the last page and have read the final lines, you will sit shaking your head for several minutes afterwards feeling a mixture of shock and admiration. And then you’ll never forget it. (Incidentally, do not read any reviews or analyses of the book first, as they may give away information that will affect your experience reading it.)

The story is told by Harry Jordan, a failed artist who now finds himself living a dissolute existence working odd jobs while dwindling into alcoholism. Late in the novel, Harry sits in prison waiting to be tried for murder. He’s convinced he will be found guilty and sent to the gas chamber. As he repeatedly tells jailers, lawyers, and other visitors to his cell, he actively desires such a fate. Knowing that he is about to die finally permits Harry to stop concerning himself with life -- something that had only barely concerned him previously, anyhow.

The day before his trial, Harry receives an unannounced visit from a man named Mr. Dorrell, an editor for something called He-Men Magazine. The magazine is interested in an “as-told-to” exclusive from Harry. They are willing to pay Harry one thousand dollars for such a story.

Harry rapidly dismisses Mr. Dorrell and his offer. He then reflects on the editor’s visit. “What kind of a world did I live in, anyway?” Harry asks the reader. “Everybody seemed to believe that money was everything, that it could buy integrity, brains, art, and now a man’s soul. I had never had a thousand dollars at one time in my entire life. And now, when I had the opportunity to have that much money, I was in a position to turn it down. It made me feel better and I derived a certain satisfaction from the fact that I could turn it down. In my present position, I could afford to turn down ten thousand, a million . . . ”

As Harry here explains, money no longer has significance for him, thus affording him a freedom to act as he wishes. Money meant little to him before (i.e., the rent, bottles of booze, the occasional steak). But now that he’s “in a position to turn it down,” Harry can act without worrying about consequences. Ironically, it is only here in prison that Harry finally begins to feel free of the constraints holding most of us back.

We think back to mythical characters like Stuey Ungar, the man Johnny Moss said had “alligator blood in his veins.” (Rounders steals this line, actually, when Teddy KGB says the same thing -- with undue hyperbole, I’d suggest -- to describe Mike McDermott.) At the end of The Biggest Game in Town, Alvarez describes Ungar’s victory in the 1981 World Series Main Event. When asked by reporters what he planned to do with the $375,000 that came with the bracelet, “Ungar ducked his head again, giggled, and muttered into his chest, ‘Lose it.’” The reporters don't seem to understand, so Ungar quickly revised his answer with a facetious “I’m gonna put it in the bank and give it to my kids, what else?”

Ungar, of course, mostly lived his life the way Harry Jordan is finally able to there in prison -- as if perpetually aware of an execution looming in the not-too-distant future. According to James McManus, Ungar played in only thirty or so NL hold ’em tourneys with $5,000 or higher buy-ins, and he won nine of them (including the three WSOP Main Event titles). Ungar obviously possessed enormous natural gifts (“preternatural,” actually, says McManus). But he also believed himself nearly always to be in a position not unlike Harry Jordan’s near the end of Pick-Up, able to “afford to turn down ten thousand, a million” (even when -- as explained in Nolan Dalla and Peter Alson’s biography of Ungar, One of a Kind -- that wasn’t always precisely the case for Ungar).

Enjoy the show tonight, if you happen to watch. And, as you evaluate the play, try not to think about the money.

No comments:

Post a Comment