Marlowe sarcastically describes Moose as “a big man but not more than six feet five inches tall and not wider than a beer truck.” Standing there on the street, staring up at the sign, Moose attracts a lot of attention. “He was worth looking at,” says Marlowe. “Even on Central Avenue, not the quietest dressed street in the world, he looked about as inconspicuous as a tarantula on a slice of angel food.”

One sometimes runs into Moose Malloy-types at the low limit hold ’em tables, those players whose play is so erratic as to attract and keep everyone else’s attention at all times. I’m talking about a particular kind of (usually losing) player. The kind who enter almost every pot, even if it means cold-calling three bets to do so. The kind who routinely call to the river with bottom pairs, overcards, or draws, and who’ll even call your river bet with a Jack-high busted draw. The kind who appear utterly unconcerned or unmindful of all of those things you are sitting there thinking about as you play. Stuff like pot odds. Position. Hand selection. Other players.

When you finally get pocket kings and this Moose is at your table, you know before the hand begins that you will at least have to outlast him/her to win the hand. You know unless the board is a nightmare you’re gonna be showing down your cowboys with Moose. You know this because Moose is showing down nine out of every ten hands.

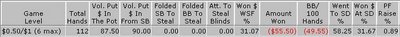

These players are also conspicuous in your Poker Tracker stats, standing out from the crowd with what seem to be unbelievable numbers (and, almost always, enormous losses). Here’s an example, a player whom I sat next to for 112 hands the other day at a $0.50/$1.00, 6-max limit table on Party Poker:

These are actual stats (click the pic to enlarge). Voluntarily put money in the pot 87.5% of the hands -- that’s 7 out of 8. Almost never folded to a raise from the small blind, and not once from the big blind (so obviously, position wasn’t much of a concern to Moose). Went to showdown nearly 6 out of 10 times, and won about half of the time. That most of the wins came on bad beats should be understood. Notice that preflop raise stat -- less than 1%. In other words, Moose only preraised once in 112 hands. (Don’t know what Moose had that hand -- it was from the BB, and s/he won the hand without having to show. Had to be aces, I’d imagine, one of the few hands we never saw Moose showdown.)

Other stats are similarly jawdropping. I sometimes like to review Poker Tracker’s “aggression factor” statistic (you get to it by clicking on “More Detail” in the “General Info” section). PT counts up the number of times a player gets to act and makes a simple calculation: Raises + Bets / Calls. Do more raising and betting out, and less calling, and you get a high number; do more calling than raising or betting, and you get a low number. PT suggests that a number of 0.70 or below indicates passive play, while a number 1.50 or above indicates aggressive play. What was Moose’s “aggression factor”? 0.24. That’s right . . . out of 500 possible actions, Moose only raised nine times (1.8%) and only open bet 58 times (11.6%). Meanwhile, Moose called or checked 395 times (79%) and only folded 38 times (7.6%).

Obviously, Moose was a big loser during this particular session, as one would expect of anyone playing in this fashion. How did I do against Moose? Well, I did have position on him/her (I was sitting to his/her immediate left), although position tends not to mean as much against players who never raise and always call. Like everyone else at the table, I had numerous showdowns with Moose, taking some decent-sized pots but also suffering some brutal beats. Won a $15 pot when I flopped a set of tens and Moose called me down with an underpair. Lost an enormous, three-way pot ($28) when I flopped a set of kings and Moose made a straight on the river. In the end, I only took $2 of the $55.50 Moose left at Table Rain Boots that day -- winning $29.50 from him/her but dropping $27.50 (!). (In fact, I ended up a $10 loser overall at the table, probably the only player other than Moose not to take a profit during this stretch of hands.)

What does all of this mean? For one, you gotta demonstrate some patience with players like Moose. In Farewell, My Lovely, Marlowe understands this truth about Moose Malloy. He might be a bit soft (particularly in the brains department), but Moose and guys like him often can be highly destructive. Later in the novel after Marlowe discovers Moose has killed Jesse Florian, Marlowe reflects “he probably didn’t mean to kill her,” but that Moose is “just too strong.” These wild, unthinking players can create similar havoc at the table -- without meaning to, probably. One simply has to resist making any gratuitous moves against them. Bluffing is out of the question. Check-raising or slow-playing is usually not a good idea, either (although it can maximize one’s profit now and then). I haven’t broken down the entire session, but I likely became impatient in a few of my “battles of the blinds” with Moose and lost chips unnecessarily. Chips Moose then swiftly handed back to the rest of the table.

One also has to be careful not to get too carried away trying to isolate the Moose Malloys -- e.g., raising medium-strength hands only to be caught in three-way pots involving both Moose and a smarter, craftier player. Remember, just because you see the tarantula on the piece of angel food cake doesn’t mean no one else has. That other player has also pegged Moose as a ready mark -- and knows that you have, too -- and so likely has some sort of plan when entering a pot with the two of you. I’m sure I lost other pots in this fashion, watching Moose limp and then raising up a hand like QT-offsuit from the button only to have one of the blinds come along and take us both down with KQ (or better) once a queen hit the board. Know that Moose is gonna be there, crashing around the china shop, making every pot three times what it ought to have been. But know that others know, too . . . .

Finding these players now and then can be great. And they do come around -- every 20 or 30 tables or so, I’d guess. But finding one doesn’t always automatically translate into the big payoff. And if you don’t like the increased volatility these Moose Malloy-types introduce into your life, you might well consider just walking the hell away. Tarantulas are poisonous, after all.

Image: Raymond Chandler, Farewell, My Lovely (1940), Amazon.

Yes, having a Moose at the table can sometimes change the entire game/make it into something completely diff. from what we're used to playing. (And I agree, the new game isn't always so fun to play, unless you happen to be one of those benefitting . . . .)

ReplyDeleteNever does any harm to rememebr what these mavericks can do. Presumably their kicks are gained not from winning money (I assume that bankroll is not an issue with them) but from the big pots they take from time to time.

ReplyDeleteThe buzz is gained not from the strategy but from the look on your face they imagine is there when they take you down.

The most annoying thing is that when you do the same to them they're probably not at all bothered.